Visual Communication

Visual

Communication

Prepared

for: Ms Nor Tijan Firdaus

Prepared By

: Evans Tiang Le Yee

Amos Walter

Goh

Shaw Kuang

Oscar Gan Chuan Song

Amanda Soimil

Weekly Task

Introduction

Even If

there is only one point, one mark on a blank page there is something built into

the brain that will meaning for it, and seek some kind of relationship or

relationship or order, if only to use it as a point of orientation in relation

to the outline of the page. If there are two point, immediately the eye will

make a connection and ‘’see’’ a line. If there are three point, it is

unavoidable to interpret then as triangle; the mind supplies the connection.

This compulsion to connect parts is described as grouping, or gestalt.

Eyes/mind

use to group points into meaning. There include Closure, in which the mind

supplies missing pieces to complete the image—this is occurs in the Mona Lisa

images to the right. A second concept is continuity—this describes the tendency

to ‘’connect the dots’’ and so accept separate parts or points as part of a

contour or form. It is hard to resist, for example, the compulsion to see two

dots as implying a line, or three as framing a triangle. Similarity describes

the tendency to see and group objects of similar shape or color. Proximity

result in a tendency to group points or objects that are close to one another

relative to less proximate in the visual field. Alignment, either along edges

of the objects or points or through their centers, will persuade us see them as

a contour or a line. For a further discussion of Gestalt theory and some visual

examples, go to this site.

Things get

more interesting when we add more than one dot and they interact with each

other. 2 dots near each other shift the emphasis of the relationships of the

dot with its surrounding space to the relationship and interaction between dot.

2 dots imply a structure. As the space between dots decreases the tension

between them increase. As that space approaches zero the tiny bit of space

itself becomes more important than either dot or any other interval of space on

the page. All the tension is held in that tiny bit of space.

As dots get

closer together they start to be seen as a single object. Their identity moves

to that of the single object instead of the multiple identities of distinct

objects. If we allow the dots to continue to get closer until one dot overlaps

the other, the tension in the space between them decreases, replaced by a new

tension based on the appearance of depth. One dot overlapping another creates a

figure/ground relationship. One dot is now in the foreground and the other is

pushed into the background. Overlapping dots form more complex shapes that

either of the individual dots. This resulting cluster of dots is in itself a

new dot with a different form.

Point is

not a very expressive design element itself but used in multiples they can

either create order in a map or create warm, natural pattern in rendering. This

is great if designer wants to create a more hand-made feeling in their design.

Point can

used to create texture and shade at the same time in rendered images. Point

Impressionist French painter Georges Seurat was a pioneer of making pictures

out of dots paint. This detail from La Parade de Cirque 1887-89, shows the way

he worked in a style called ‘pointalism’. A detail(right) shows how colored

lights/pixels combine to form an image on an LCD screen.

Points or

dots are also used to order a range or topics without a numeric hierarchy. Dot

or ‘bullet’ points can be circular or use any other image to attract attention.

Point is used to identity or locate something. The density and contrasts of the

mark steers the viewer’s vision to the information being communicated. Points

are used to represent something complex – for example towns on a map.

Line

The

Vocabulary of Line

Line begins

with a dot and describes the motion of that dot shows the connection between

that one dot to another. Line come together with point, is a basic concept of

elementary geometry. The idea of line is an abstraction that distills our

intuition that a straight line is the shortest way between two points. However,

we distinguish between a line and a line segment. A line segment includes the

endpoints, i.e. the points that it joins. The line through the two points

continues beyond these points indefinitely.

The artist can use line to resent complex

ideas, record something deserved, or simply document, or action. An objective

use line can describe simple measurement and surface characteristics and can

indicate a sense of depth.

The

physical characteristics of line are many. Lines may be short or long , thin or

thick , straight or curved. These characteristics have curtain built-in

association that the artist may make use of. In most cases, we have adjectives

that fit the lines we see. And, like the word associations just cited, those

meanings are part of line’s subconscious power suggestion.

Measure

refers to the length and width of line –its measurable properties. A line may

be of any length and breadth. An infinite number of combinations of long,

short, thick, or thin lines can, according to their application, unity, divide,

balance, or unbalance an image. Indeed, an emotional dynamic is set up by

line’s measure. For example, thick lines tend to communicate more of sense of

stability than thinner lines. When applied to the development of typeface, a

thick font seems more forceful than a thinner one.

There are

many different types of line. If the line continues in only one direction,

gradually occur, it is curved; if those changes are sudden and abrupt, an

angular line is created. By joining the characteristics of measure and type, we

find that long, in its continuity, ultimately seems stiff and rigid and, if

rendered thinly, may appear brittle. The curved line may form an are, reverse

its curve to become wavy, or continue turning within itself to produce visually

entertaining and physically stimulating if they are rhythmical. A curved line

is inherently graceful and, to a degree, unstable. The abrupt changes of

direction in an angular line create excitement and/or confusion. Our eyes

frequently have difficulty adapting to an angular line’s unexpected deviations

of direction. Hence, the angular line is full of challenging interest.

The specific

location of a line can enhance or diminish the visual weight and our

psychological response to the other characteristics of the line. In Chapter 2 we

saw that the location of an image on the picture plane, with regard to the

effect of gravity, could create emotional responses ranging from excitement and

anticipation to relief and calmness. Line is affected by its location in the

picture plane might appear to be soaring, while that same line placed in low

position might appear to be plunging.

Along with

measure, type, direction, and location, line possesses character- a visual

surface quality related to the medium with which the line is created. Each

instrument –brush, burin, stick, pencil, finger, and so forth –has distinctive

characteristics that respond in different way to different surface. As such,

the character of a line can vary from chalk’s grainy dots of varying destiny to

the feathery reticulated edge of an ink line bursting across a wet surface.

Some media, like ink, can provide a wide range of textures and edge qualities,

from soft and blurred to sharp and crisp, while other media, like an assortment

of pencils or content crayons, have a depending on the pressure applied and the

hardness of the drawing material.

Shape means

defined as an area that stands out from the space next to or around it. A shape

is formed when a line cross each other. Shape can be geometry or organic such

as the shape of a puddle, blob, leaf and other.

The degree

of lightness or darkness that a line exhibits against its background is called

value. A change in value. A change in value helps a line stand out from its

surroundings-the greater the contrast, the more visible the line. Value differences

can result from layers and mixtures of media, the amount of pressure exerted on

the tool , or line characteristics (wide, heavy line appear dark in value, and

narrow lines appear lighter in value).

Groups of

lines can combine can combine to create to create the illusion of a visual

texture, suggesting tactile feel for an image. Visual texture can indicate

degrees of roughness or smoothness that simulate our sensation to touch.

Regardless of whether it is invented or based on something seen, a work ‘s

texture can be enhanced by the choice of the medium and the way in which it is

used. The texture of marks made by hard bristled brushes can range from sharp to

rough, depending on the pressure applied and the type of paint medium used.

Soft-haired brushes can produce smooth textured lines with thin paint and thick

blotted lines with heavy, viscous paint. When line translated into any new

medium, it has its own unique texture quality. Compare the texture of etched

line to the linear texture of brushwork or the texture of brushwork or the

textural lines created on a woodcut. Although each of these works relies

heavily on line, the differences in tools and media vastly affect the way in

which the lines create texture.

The

introduction of color to a line adds an important expressive potential. Color

can accentuate other line properties. A hand (crisp, sharp, or distinct) line

combined with an intense color produces a forceful or even harsh effect. This

effect would be considerably muted if the same line were created in a neutral

color. In addition, colors have come to be identified with different emotional

states. Thus, the artist might use red as a symbol of passion or anger, yellow

to suggest cowardice or warmth, and so forth.

Depending

on their application, physical characteristics of graphic line can create a

sense of space. Thick lines tend to advance forward spatially, while thinner

lines in the same medium tend to recede by comparison. A line that modulates

from thick to thin will become very active spatially, and when combined with

changes of value, the darker, thicker portions become even more dynamic. Value

contrast alone can cause a line to advance and recede, and an individual line

with varied values throughout its length may appear to writhe and twist in

space. A line that curves and twist can even appear to move away from the

viewer, especially if the width of that line varies. In addition, texture and

color contribute to a line’s spatial effect: a line with greater textural

detail can suggest distance; and warm colors generally advance, while cool

colors generally recede.

Line

Creates representation on both realistic and abstract levels. The lines drawn

in an architect’s plan for a building can symbolize walls or construction

materials; the lines drawn in maps can represent rivers, roads, or contours;

and the lines that form letters and words in a textbook can represent thoughts

and concept. Such use of line is primarily utilitarian, a convenient way of

communicating Ideas to another person.

Artist may

indicate a wealth of factual information by employing a variety of line

characteristics. For example, in a map of London’s train system, differences in

the line color, thickness, length, and value convey specific, practical

information to a rider. The variety among the lines makes it easy for a person

to see a route or connecting points.

Shapes are

often referred to as the building blocks of art structure. Like the bricks,

stone, and mortar used to construct architectural edifices, shapes in art build

strength into the structure of the composition. With careful placement and

treatment, shapes also create various illusions of depth and dimensionality and

engage the viewer though their expressive nature.

As artist

begin their work, they frequently have some preliminary vision of shape,

whether planning composition-wide pattern or just thinking about individual subject.

The artist may have a clear concept in mind for an abstract image and know

instinctively what shapes will give that idea substance and structure. Or he or

she may prefer an evolving reveal themselves though experiment.

The

configuration of a shape’s outer edge helps give it a character that

distinguishes it from others. When the shapes used by an artist imitate

observable phenomena, they may be described as objective, naturalistic,

representational, or realistic, depending on the context. However, when shapes

are more imaginary or seem to have been invented by the artist, they are often

called subjective, abstract, nonobjective, or non-realistic. Shapes may also

belong to a number of other categories or families of shape type, according to

the configuration of their edges.

Shapes may

also have either two-dimensional or three dimensional identities. In pictorial

artwork, shapes are created on the two-dimensional picture plane; however,

artists may create the illusion of mass, volume, and space on their flat

working surface though the careful juxtaposition and treatment of

two-dimensional shapes. When we use the term mass to describe shapes on the

picture plane, we mean that they have the appearance of solid three-dimensional

bodies. The term volume, on the other hand, describes what appears to be a

three-dimensional void, or an amount of measurable space. Rocks an mountains

are masses, while holes and valleys are volumes; cups are masses, while the

amounts of space they contain are volumes.

Shapes

often become a key element in the structure of a unified composition, like the

pieces in a building’s foundation. Their placement and physical characteristics

help a sense of harmony, variety, balance and so forth. So important are shapes

to composition that the contour of the picture frame is among the first

considerations an artist must make, and that choice affects the relationship of

all images and elements developed within. For example, a horizontal frame harmonizes

with horizontal images, shapes, or linear movements and makes vertical shapes

stand out as accents in relief. The repetition of general directional forces

thus becomes a factor for harmonizing the inside with the outsides. For the

reason, landscapes, reclining figures, or abstract images that move across the

image are more easily developed within a horizontal rather than a vertical

frame. Likewise, vertical picture frames encourage harmony with vertical

components and the use of horizontal marks or shapes stand out as accents.

Portraits, tall still lifes, and stained-glass windows are examples that work

well within a vertical frame. However, exceptions can be found for very

convention, so these observations are offered only as guidelines.

The

repetition of similar shapes is an easy way to create a sense of harmony in

most composition. When shapes share similar edge characteristics, they seem to

belong to a related group and may be referred to as a ‘’shape family.’’ As with

members of a human family, the likeness need not always be identical but merely

enough to see their relationship. By using the same number of sides on each

shape by using similar contour qualities, the shapes will appear to belong

together. Their similarity in structure can then be enhanced by common

applications of value, texture, or color.

Artists

develop dominance intuitively as they respond to each area and shape within a

composition, using the principles of organization, from harmony and variety to

economy. Obviously, the relative dominance of shape may be altered by contrasts

in size color or value, visual detail, texture emphasis, directional force, and

so forth. But on a more basic level, simply changing the design of one shape

can make it the dominant member among a group of similar shapes. Because the

degree of dominance is established by the degree of contrast, the amount of

change within the shape family helps establish the amount of each new shape.

The more similar a shape is to its neighbors, the less dominant it is.

Artist can

use shape, along with the other element of form, to generate visual forces that

direct our eyes as we view the work. Some shapes, like circles and squares, are

excellent at anchoring or holding a location in a composition. Because of their

stable nature, nature they can also establish tension and create subconscious

movement: when other shapes are located close enough to these focal point, the

eye bounces back and forth, trying to make them join together or become part of

a group relationship.

In the

search for composition balance, artist work with the knowledge that a shape’s

visual weight is used, the development of the negative area around it and how

the elements of art are used in composing both. The placement, size, accent or

emphasis, and general shape all affect the amount of visual weight a shape has.

A dark value adds weight to a shape; substituting a narrow contour the shape’s

visual weight; and an amorphous edges can reduce the sense of focus on that

shape and thereby reduce its visual weight and degree of dominance.

When trying

to develop appropriate proportions and a sense of economy, and artist may

benefits from breaking down the subject into simple planar shapes. This allows

the vastness and intricacies of a subject to be simplified for easy translation

onto the picture plane and provides a method for studying the composition arrangement of those shapes. Working from light to dark, general planar shapes

are blocked in, one layer at a time. In each succeeding the lighter shape

become more defined as their contours are articulated by the darker shapes that

surround and overlap them. In the end, shape layers indicate not only the

overall scene but also the relationship of humans to nature, and the image

becomes quite refined.

While a

shape’s physical characteristics may be easily defined, its expressive

character Is rather difficult to pinpoint, because viewers react to the

configuration of shape on many different emotional levels. In some cases, our

reactions are complex and individual because of our own personality and

experiences. The familiar Rorschach (inkblot) test , which was designed to aid

psychologists in evaluating emotional sensitivity to shapes. The test indicates

that shapes provoke emotional responses on different levels. Thus, the artist

might use specific abstract or representational shapes to provoke a desired

emotional response. By using the knowledge that some shapes are inevitably

associated with certain feelings and situations, the artist can set the stage

for a pictorial or sculptural drama. The full meaning of any shape, however,

can be revealed only though the relationships developed throughout an entire

composition.

Texture is

one of seven elements of art. It may be unique among the art elements because

it immediately engages two sensory processes – sight and touch. It is used to

describe the way a three-dimensional work actually feels when touched. At its

most basic, texture is defined as a tactile quality of an object's surface. It

appeals to our sense of touch, which can evoke feelings of pleasure,

discomfort, or familiarity.

In

painting, drawing, and printmaking, an artist often implies texture through the

use of brushstrokes lines as seen in crosshatching. When working with the

impasto painting technique or with collage, the texture can be very real and

dynamic. Texture may refer to the visual "feel" of a piece. Take a

brick as example. A painter depicting a rock would create the illusions of

these qualities through the use of other elements of art such as color, line,

and shape to create the feeling of hard and heavy of the rock.

In

three-dimensional art, texture is very important, you can’t see one without it.

The materials used decide a piece of art texture. The materials that mostly

used by the artist is marble, bronze, clay, metal, or wood. The material

decided what the feeling we feel when we touch it. The artist can add more

texture through technique. One might sand, polish, or buff a surface smooth or

they might give it a patina, bleach it, gouge it, or otherwise rough it up.

As in art,

you can see texture everywhere. You can feel texture everywhere. We usually not

consciously aware of it. The smooth leather of your chair, the coarse grains of

the carpet, and the fluffy softness of the clouds in the sky all invoke

feelings. [i]

There are

four basic type of texture that artist used in their artwork.

Actual

Texture is the “real thing”- a surface that can be experienced through the

sense of touch. It is not an illusion created by drawing or painting. Many

works of art depends heavily on the actual texture of the medium. For example

wood, glass, fibers. The actual texture will changed when an artist paint or

draw on the medium. The paint on the surface will drastically change the texture

on the surface, for example impasto style. On the other hand, the drawing will

also change the surface of the medium in a more subtle manner. In early

twentieth century, the actual texture is used along with the paint. Picasso

pasted a paper to drawing, it is a first example of paper collage. it is later

expand to the use of newspaper, magazine, poster and so on. The artist is later

expand to use actual texture from wide range of materials and combined it with

paint to create artwork. For example, Still Life by Pablo Picasso, 1918.

Simulated

Texture is an imitations of the real object. There are some technique in

reproduce the texture, which is stamping and tracing on the texture. But these

technique is limited on the rough surface. Some of the artist will skillfully

reproduced the texture of the “real” object. For example Andrew Newell Wyeth ‘s

artwork, Snowflakes 1966. The simulated texture seem real but it may be just a

two- dimension surface. Simulated Texture is very useful for interior designer.

The Simulated Texture of rock or stone help designer decorate the wall.

Abstract

Texture is a texture that reproduced by the artist. But instead of reproduce

the actual texture. The artist reproduce the texture that only display some

hint of the original texture and is modified to suit the artist’s needs. The

abstract texture is normally simplified version of the original. The artist

emphasis the pattern or the design of the texture. For example Roy

Lichtenstein, Cubist Still Life with lemons, 1975. In these artwork, the

textures function is in a decorative way. The abstract texture can be used to

accent some area to accent some area.

Invented

texture is texture without precedent, they do not simulate, nor are they

abstracted from reality. They are purely creation of artist’s imagination/ it

useaky upper in abstracted a non-objective works. For example, Brian Fridge,

Valt Sequence No. 10,2000. Black and white silent video four minutes. DVD.

Both

texture and Pattern developed through light and darks. Pattern is decorative

and not concerned with surface texture but with appearance. Texture is normally

associated with impression of three dimensionality of surface. Lights and Darks

indicate the various reflections and shadows created by peak and valleys of the

object.

Aside the

ability to stimulate our sense of touch, texture can add emphasis and emotion

to the composition. The use of texture can influence a composition, creating

harmony, variety, and interest. Texture can be added to make an artwork more

life. For example, The Picasso’s Dog and Cock is a good example. It draws our

eye to more significant parts of the painting.

Texture

have symbolic or associative meanings, they can provoke psychological or

emotional response that can be pleasant or unpleasant. It usually associated

with environments, experience, objects or persons from our experience. Texture

as a device that enhance and alter the expressive content of the artwork on a

subconscious level. The artist can use texture to stimulate our curiously,

shock us or revaluate our perception, like the artwork from Vik Muniz. He uses

chocolate syrup as a drawing medium.

INTRODUCTION

Point

Task 1: Point

Sense Of Line

Sense Of Movement

Illusion Of Depth

Layer By Layer

Form

Task 2: Line

Type Of Line

Emotion

Sad

Happy

Anger

Type Of Lines

Task 3: Shape

Nature Shape

Geometry Shape

Organic Shape Combination

Geometric Shape Combination

Final Combination

Task 4: Texture

Actual Texture

Abstract Texture

Final Texture

INDIVIDUAL TASK

Name: Amanda Soimil

Point

Line

Name: Amos Dungkian Walter

Point

Line

Name: Evans Tiang Le Yee

Point

Line

Name: Oscar Gan Chuang Song

Point

Line

Name: Goh Shaw Kuang

Point

Line

⧭THANK YOU ⧭

Programme Name : VISUAL COMMUNICATION

Programme Code : DNM111

TITLE : FINAL RESEARCH BOOK ( ASSIGNMENT 1 )

Prepared for :

Ms Nor Tijan Firdaus

Prepared by :

Amanda Soimil

Amos Dungkian Walter

Evans Tiang Le Yee

Oscar Gan Chuang Song

Goh Shaw Kuang

Final Research Project

1. Visual Data Collection

1.1 Introduction

- Content

- Idea

- Form

1.2 References

2. Process

2.1 Form Studies

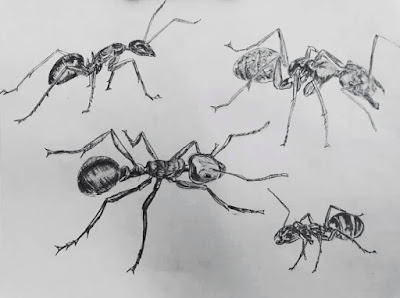

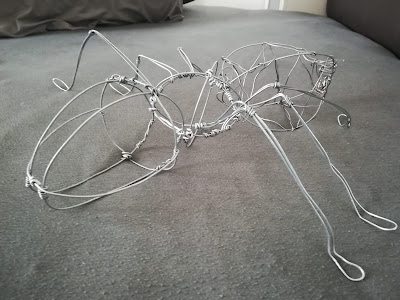

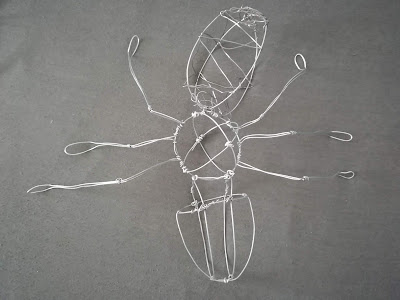

- Sketches

- 3D Wire Sculpture

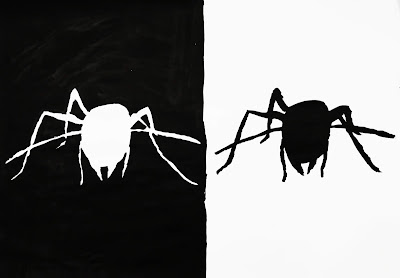

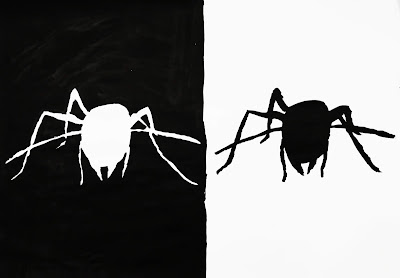

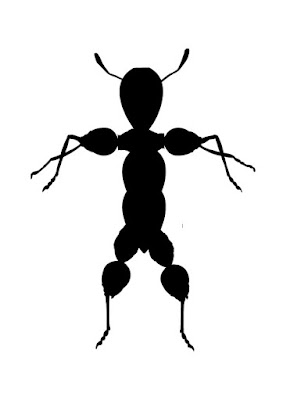

2.2 Stylization

2.3 Simplification

2.4 Composition

3. Finding

3.1 Final Outcome

1.1 INTRODUCTION

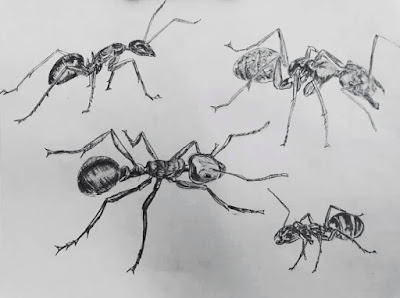

Ants are eusocial insects of the family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from wasp-like ancestors in the Cretaceous period, about 140 million years ago, and diversified after the rise of flowering plants. More than 12,500 of an estimated total of 22,000 species have been classified. They are easily identified by their elbowed antennae and the distinctive node-like structure that forms their slender waists.

Ants form colonies that range in size from a few dozen predatory individuals living in small natural cavities to highly organised colonies that may occupy large territories and consist of millions of individuals. Larger colonies consist of various castes of sterile, wingless females, most of which are workers (ergates), as well as soldiers (dinergates) and other specialised groups. Nearly all ant colonies also have some fertile males called "drones" (aner) and one or more fertile females called "queens" (gynes). The colonies are described as superorganisms because the ants appear to operate as a unified entity, collectively working together to support the colony.

KEY IDEA

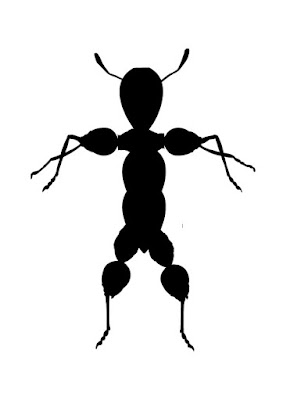

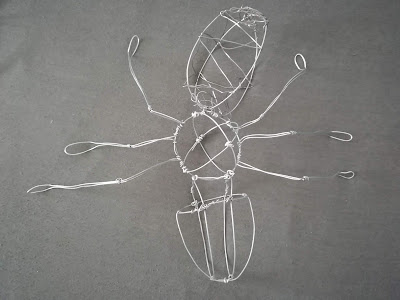

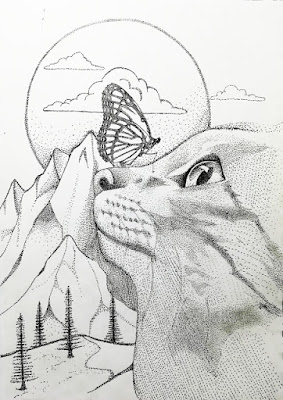

After a group discussion, we have decided to choose ants as our form and visual ordering. Ants are eusocial insects of the family Formicidae and, alongwith the related wasps and bees, belong to the order Hymenoptera. Ants are exoskeleton creature which has 3 pair of legs and a pair of antennae.

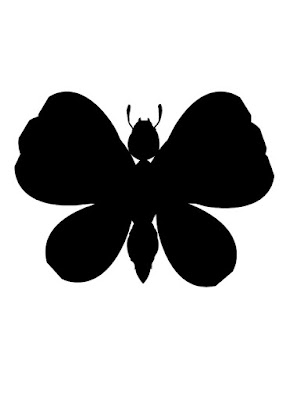

As in all insects, an ant's body is divided into three main parts: the head, the thorax,and the abdomen. The thorax is composed of three segments, each with a pair of legs. Since most of the ants have their own unique colors, it can be reference while doing stylization for the ant. We did a lot of research from the website while forming the different views of ant by using wire. The simplification of the views of the butterfly can form up into other object's shapes so we make use of it and do composition for it.

Afterwards, we gather ideas and take the composition outcome as reference, we planned out the form of the final outcome for this project.

FORM

Now that you can see how ants are put together and what each part is named, let’s learn what each part does and what is inside of them.

The ant’s second body segment, the mesosoma, is packed full with muscles that power its three pairs of legs. The legs are designed for running – ants can run very fast for their size. At the end of each leg is a hooked claw that is used to climb and hang on to things.

The head of an ant is similar in some ways to our own heads. It's the first segment on the ant, and it contains sensory organs. On our own heads, our sensory organs include eyes, ears, a nose and a mouth. An ant has eyes as well, but they are compound eyes. This means that instead of each eye having one lens like ours, it has many lenses attached.

An ant also has a mouth, with special mouthparts called mandibles. These parts are used for cutting, grabbing and biting.

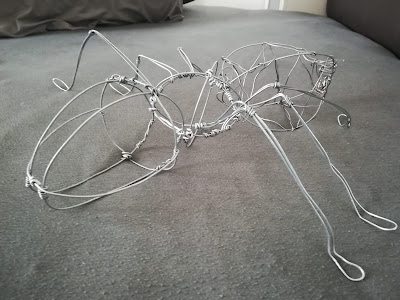

2.1

2.2

3D Wire

Simplification

2.4 Composition

Process

3.1 Final Outcome

Comments

Post a Comment